Thinking, Fast and Slow

In the book Thinking, Fast and Slow, the author, Daniel Kahneman, talks about the experiencing self and remembering self. Kahneman first recalls a study involving patients undergoing a painful colonoscopy, for which at the time of the study there was little anesthetic or other drugs to ease the pain. Every 60 seconds patients were asked to record their pain on a level of zero, indicating no pain, to ten, indicating intolerable pain. The experience for each patient varied considerably, with the shortest lasting 4 minutes and the longest lasting over one hour. These measures based on reports of momentary pain were called hedonimeter totals. Surprisingly, the feedback from the patients was not as anticipated.

The Peak-End Rule and Duration Neglect

Kahneman writes:

When the procedure was over, all participants were asked to rate “the total amount of pain” they had experienced during the procedure. The wording was intended to encourage them to think of the integral of the pain they had reported, reproducing the hedonimeter totals. Surprisingly, the patients did nothing of the kind. The statistical analysis revealed two findings, which illustrate a pattern we have observed in other experiments:

- Peak-end rule: The global retrospective rating was well predicted by the average of the level of pain reported at the worst moment of the experience and at its end.

- Duration neglect: The duration of the procedure had no affect whatsoever on the ratings of total pain.

Experience or Memory?

Kahneman recalled a short anecdote, also alluding to the same phenomenon:

A comment I heard from a member of the audience after a lecture illustrates the difficulty of distinguishing memories from experiences. He told of listening raptly to a long symphony on a disc that was scratched near the end, producing a shocking sound, and he reported that the bad ending “ruined the whole experience.” But the experience was not actually ruined, only the memory of it. They experiencing self had had an experience that was almost entirely good, and the bad end could not undo it, because it had already happened. My questioner had assigned the entire episode a failing grade because it had ended very badly, but that grade effectively ignored 40 minutes of musical bliss. Does the actual experience count for nothing?

As with the medical patients, the retrospective rating was influenced by the peak-end rule. Kahneman notes that mixing up experience with memory is a common cognitive illusion. Here is the problem:

The experience self does not have a voice. The remembering self is sometimes wrong, but it is the one that keeps score and governs what we learn from living, and it is the one that makes decisions. What we learn from the past is to maximize the qualities of our future memories, not necessarily of our future experience. This is the tyranny of the remembering self.

The Cold-Hand Experiment

This idea led Kahneman and his colleagues to design an experiment where participants submerged one hand in painful but not intolerable cold water for a certain length of time. The participants used their free hand to record the amount of pain they were feeling while the experiment occurred. The participants had two trials. For one, a hand was submerged 14° Celsius water for 60 seconds, after which time they removed it and were given a warm towel. The other trial was for 90 seconds, and while the first 60 seconds were identical to the other trial, the last 30 seconds the experimenter released a valve that warmed the water 1°, a noticeable difference which slightly decreased the pain. Then the participants were asked how they wanted the third trial: exactly the same as the first or exactly the same as the second.

The first two trials were very controlled. Half the participants experienced the 60 second trial first and the 90 second trial second, and the other half vice versa in order to prevent the sequence of experience influencing the choice for the third trial. In addition, the experiment was designed to conflict the two selves. The experiencing self obviously had a more painful time during the long trial. If the first 60 seconds are the same, why endure the extra 30, even if they are slightly less painful? However, based on the peak-end rule, the long trial is preferable because the ending wasn’t as painful as the short trial, with the peaks being equal.

What did they participants choose for the third trial?

They choose the long trial. “Fully 80% of the participants who reported that their pain diminished during the final phase of the longer episode opted to repeat it, thereby declaring themselves willing to suffer 30 seconds of needless pain in the anticipated third trial.”

Why the discrepancy?

The remembering self had a more favourable memory of the long trial, despite the duration, due to the peak-end rule. Even though this conflicted with the experiencing self, the remembering self is the one that makes the decisions.

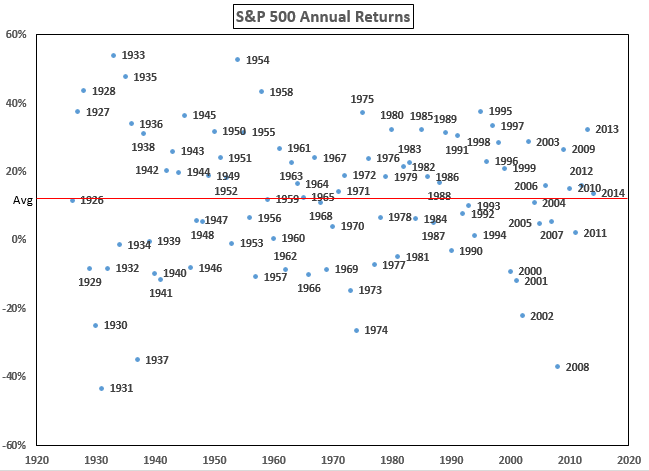

A somewhat recent post from Ben Carlson triggered me to think of how the discrepancies between the experiencing self and remembering self might be present in investing. In Playing the Probabilities, a post he wrote earlier last month, Carlson used this chart:

It is a solid visual, but one thing really stood out to me - the annual returns were rarely close to the average, represented by the red horizontal line.

To be specific, looking at data compiled by Aswath Damadoran outlining the S&P 500 annual returns from 1928 to 2014, the geometric average of those numbers is 9.60%. However, the individual annual returns tell a different story.

Only one year over this 80+ year time horizon was the annual return within 1% of the average annual return over the same time horizon: 1993 with a 9.97% return. Only three years over this 80+ year time horizon was the annual return within 2% of the average annual return over the same time horizon: 1993 at 9.97%, 1968 with a 10.81% return, and 2004 with a 10.74% return.

What can we conclude?

Asset allocation requires the use of risk and return assumptions. However, maybe we need to consider the differences between the experiencing self and remembering self. I think most would agree that returning 7.7% in year one and 12% in year two is a different investing experience than returning -10% in year one and 34% in year two, even though they both average out to roughly 9.8% for the two year period. While the experiencing self may go through one encounter, the remembering self may recall something different.

This is essentially what the sharpe ratio is about, calculating risk-adjusted return. A fund manager who returns 15% with a standard deviation of 10 is not equal to a fund manager who returns 15% with a standard deviation of 6. The latter is superior. If we apply the takeaways from Kahneman’s research however, the answer isn’t so black and white. The remembering self is the one that makes the decisions, and the peak-end rule may result in a preference for the former.

Kahneman writes the following:

The cold-hand study showed that we cannot trust our preferences to reflect our interests, even if they are based on personal experiences, and even if the memory of that experience was laid down within the last quarter of an hour! Tastes and decisions are shaped by memories, and the memories can be wrong. The evidence presents a profound challenge to the idea that humans have consistent preferences and know how to maximize them, a cornerstone of the rational-agent model. An inconsistency is built into the design of our minds.

Reflecting back on our investing experiences may not provide true insight into our actual experience. As Kahneman demonstrated, this is because our experience self and remembering self are in conflict. Ultimately, these ideas all delve back to the fundamental idea of investing: determining trade-offs between risk and reward. And if we can’t accurately distinguish between certain preferences, can we accurately assess these trade-offs? If you don’t understand your own risk tolerance, can someone else, such as an financial advisor, hope to do so? While, for example, new technologies, such as Riskalyze, attempt to make strides in this area, advisors need to do more as well. This means spending extra time and effort to learn about client’s risk tolerance and risk capacity, while understanding what one remembers may not be in line with what one experienced.

Thinking, Fast and Slow is a must-read for any serious investor.